The Hunter – a story from rural France

Pierre walked stiffy up and down a couple of times so that I could do this sketch. He took it all incredibly seriously and had doubtless had a bath especially. Certainly, he had had a good shave.

Shotgun in hand, these hunters set off every Sunday morning once La Chasse has started in September, right through to when the chassing season (so to speak) ends in March. Shotguns tucked under one arm, footwear varying from wellies to trainers, walking boots and good stout hunting boots (as in Pierre’s case), hats on heads, a couple of dogs apiece, off they go to see what they can kill. The older ones, and the more serious ones, and the slightly better off ones, wear khaki or dull green, bullets (well, I suppose that’s what they are) at their belts.

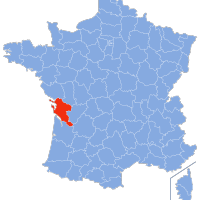

In the Charente Maritime there’s not a lot left to kill (“quick, Marie! Put an extra brick on the fire – I’ve shot a mouse!) and they usually release an assortment of caged game birds, called gibier, in to the field and then run around after them trying to get the poor creatures to take flight. And then they blast them out of the sky. All very macho.

It has always struck me as really rather silly and quite sick-making. The concept of animal rights is totally alien to the average hunter and they take their hunting prowess incredibly seriously.

Our baker gave me a dead pheasant once. In those days he used to come round in a van with croissants and baguettes and fly-encrusted tartelettes of various sorts. Without so much as a by-your-leave, or even a bonjour Madame (as the case may be), he thrust the pheasant under my nose and declared, “ca, c’est pour vous!” I took the creature in one hand, doing my best to disguise my revulsion. Oooooh, lovely, I declared, not certain why the baker was giving it to me and concerned it was part of some local Charentais ritual that I should have long since been au fait with.

“C’est un faisan!” the baker now declared, and I smiled even more broadly. Lovely, lovely, I repeated, conscious that I was doing a bit of unnecessary bobbing up and down.

“Do you know how to cook it?” the baker now leaned frighteningly out of his van window, his face close up and personal.

“No, I’m afraid I don’t” I replied as I recovered my composure and realized that the aim behind the donation of this dead bird in my hand was an entirely well-meant gesture. “But!” I held one hand up before a great tirade of cooking instructions could erupt from his mouth, “But! My mother-in-law is here and she is a brilliant cook and she will know exactly what to do.”

“You have to skin it,” he said ignoring me and half-heartedly flicking a few flies away from his tartelettes. “The skin is very tough. Pluck it and skin it.”

“Jolly good,” I said. Infact “tres bien.” I nodded vigorously to show that I understood.

“Tough!” he warned, raising one finger in the air, “and the taste is no good either. So skin it properly. After you’ve plucked it.”

I looked at the poor bird. The neck hung over my wrist and a small quantity of dried blood emerged from its beak. Yuk. A couple of flies had started to buzz about me.

“I’ll have two baguettes,” I said, determined to get away before he started on any further admonitions.

He handed the baguettes to me. I noticed a couple of small feathers stuck to his fingers. For a dreadful moment I thought that perhaps I should invite him to eat the pheasant with us. Surely not ? I glanced quickly at the bird : insufficient meat for us, let alone any guests. Goodness – was he expecting me to pay for the bird? I didn’t want it. Further flies were gathering.

“Thanks very much, monsieur,” I said, handing him the baguette money. “It’ll be delicious. I’ll let you know how it goes!”

And I turned and strode purposefully off. If he wanted me to pay for the bird, he’ll call after me, I thought. He didn’t, so I didn’t.

Inside the cool of my kitchen, Grandear, my mother-in-law, looked aghast. I turned the dead creature at a jaunty angle so that she could have a good look. That poor creature – probably kept in a cage for ages and then released only so that some idiot could ( he thinks) prove his manhood by killing it.

“Lord – I used to cook that sort of thing, but not now. It’s not that I can’t, its just that I won’t,” she said with habitual honestly.

“Right,” I said, “that suits me. In the bin, then?”

“Yes, in the bin,” she said, her lips set in a thin line, “it’s the only sensible thing to do.”

I plopped the carcass in to the dustbin, well wrapped up in case the dustman turned out to be the baker’s brother – which was highly likely. Grandear and I grinned at each other like two naughty girls who have just got out of doing homework. I wondered what the bird would have said, had it known it was going to be blasted out of the sky for the sole purpose of adorning the interior on an English dustbin.

The End

Catherine Broughton

Interested in France ? Book your holiday – go to www.seasidefrance.com